Contemporary drag culture has multiple roots, multiple legacies, and multiple histories. Drag queen culture comes out of early 19th century balls, Vaudeville, pageants, World War II soldier shows, mainstream straight-facing nightlife, trans femme culture, gay bars, Black entertainment clubs, Ballroom culture, and politicized camp traditions. Today’s drag king culture comes from jut as complicated a web of influences. Here are some key traditions and figures that shape today’s drag king culture.

1660s England: The Breeches Role

To trace the history of U.S. drag kings, we’ll start in England. As you probably know, in Shakespeare’s England women were banned from performing on stage. Men played women’s roles until the 1660s, when some actors began continuing to wear feminine clothing off-stage. As a result, the Drury Lane patent allowed women on stage. Women began taking on male parts, especially comedic roles. Usually, these women did not aim to convince anyone that they were men, instead playing up their feminine characteristics for laughs. Women in drag went mainstream – and stayed there.

The Victorian/Edwardian Music Hall

Male impersonators, as they were typically called in this time period, often played in music halls, establishments that served a mixed-class audience. In these music halls, male impersonators began to express a kind of masculinity at mainstream audiences saw an authentically male.

In England, many of the most famous male impersonators often sang and danced and took on the role of the dandy. The dandy, a fashion-conscious man of superior taste, was popularized by gay icon Oscar Wilde, another example of the intertwined history of queer and trans communities across assigned birth gender. Later, when Oscar Wilde was put on trial for his sexuality and England entered World War I, male impersonators began to favor dresses as soldier, casting themselves as patriotic and proper men.

Vesta Tilley, pictured above in both Edwardian high femme style and a top hat and tails, and was one of the most famous English male impersonators during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Tilley was deliberate to presented herself as feminine when of stage. She did not cut her hair, instead covering it with a wig. In the press, she was just an ideal a woman in her daily life as she was an ideal man on stage.

In contrast, male impersonators in the United States at this time embraced a more ambiguous, even openly queer and trans life off stage.

For example, American Annie Hindle, pictured above in military attire, wore a moustache and stubble. Hindle even married Hindle’s dresser, though, of course, their queer relationship was not legally recognized. Dressing as a man on the stage served to protected Hindle’s off-stage life.

The Blues

In the mid 1900s, the Blues provided a haven for Black performers to express their gender and sexuality more freely. This was especially true for women and queer people. Blues songs were filled with lyrics describing non-normative sexuality, from cheating to queer relationships, in both explicit and coded language. Many songs included gender ambiguous or gender-neutral terms for genitalia, like “jelly roll” in Bessie Smith’s song “Nobody in Town Can Bake a Sweet Jelly Roll like Mine.” And on and off stage, some of the queens of the blues dressed like men.

Blues singer and pianist Gladys Bentley began performing on stage when she moved to Harlem in 1925. Thanks to the Harlem Renaissance, which in Black queer people played pivotal roles, Bentley was able to quickly find a queer audience. She began performing what described as “white full dress shirts, stiff collars, small bow ties, oxfords, short Eton jackets, hair cut straight back”. Her most famous photographs, pictured above, show her in a gorgeous tux.

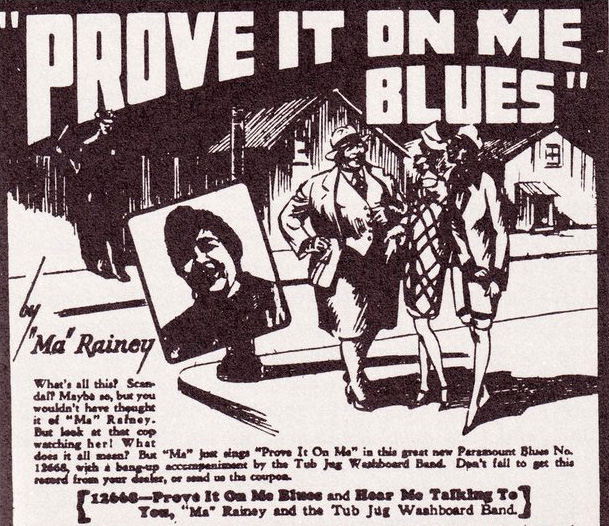

At the same time, Blues diva Ma Rainey was singing openly queer lyrics that celebrating crossdressing. Her hit “Prove it On Me” boasted about her relationships with women. The promotional photo for the song, pictured above, showed her flirting with two women while a police officer menaces.

The lyrics of “Prove It On Me” included the following lines:

They said I do it, ain’t nobody caught me / Sure got to prove it on me

Went out last night with a crowd of my friends / They must’ve been women, ‘cause I don’t like no men

It’s true I wear a collar and tie / Make the wind blow all the while

‘Cause they say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me / They sure got to prove it on me

Bentley and Rainey were not male impersonators or drag kings in the sense that we use the terms today. They presented themselves as queer women in men’s wear. Nonetheless, they were some of the biggest stars of their time. When we consider the history of drag and impact of, they demand to be mentioned.

The GOAT: Stormé Delaverie

Perhaps the most historically important male impersonator of all time was the indomitable Stormé DeLarverie. DeLarverie is not just essential to any history of drag in the US; without her, you can’t talk US LGBT history, period.

DeLarverie was born on 1920 in New Orleans to a white father and Black mother. As a light-skinned, androgynous woman, her body was often read in many different ways; she was bullied by both white and Black kids as a child and arrested and harassed by police regularly. Twice, she was arrested by cops who thought she was a drag queen. DeLarverie turned the ambiguity she was forced to live in into a source of creative and power.

After leaving home after realizing that she was a lesbian near the age of eighteen, DeLarverie joined the most famous drag show in the United States: The Jewel Box Revue. The Jewel Box Revue advertised itself as “25 Men and One Girl.” DeLarverie, who MCed the show and sang, encouraged audiences to guess who was the “one girl.” Many were shocked to find out it was her. (As a note, the Jewel Box Revue actually employed several trans women additionally. More on that in my upcoming academic book).

DeLarverie wore natty suits in her off-stage life as well. She lived with her partner Diana for 25 years, until her death in the 1970s. DeLarverie carried a photograph of Diana with her at all times. Sweet, huh?

In 1969, DeLarverie played an important role during the Stonewall Rebellion. Many witnesses reported that the first person to throw a punch at the police was a butch lesbian. It’s widely known that DeLarverie was that lesbian. She never took credit for her actions, but also did not deny it. She instead always reminded everyone that the Stonewall Rebellion was a collective, political uprising.

DeLarverie continued serving her community until her death in 2014 at the age of 93. She worked as a bouncer at lesbian bars and patrolled the streets of New York City looking out for the well-being of queer women, whom she called her “baby girls.” It is absolutely no exaggeration to say that every single queer and trans person in the United States owe a debt of gratitude to the GOAT male impersonator.

All drag royalty deserve our respect and gratitude. All hail the kings!